SUSTAINABILITY AND ARCHITECTURE

Although energy-saving buildings can now be built from largely recyclable building materials, this has not yet led to a new form of architectural expression, so the question is raised whether there is any connection at all between sustainability and drafts or designs.

In addition, there is also the question whether buildings with clearly recognisable energy-saving designs can be more easily marketed than energy-saving buildings without special design?

If we consider the market for consumer goods, we see that technical developments are most swiftly reflected in new product designs for products which are sold on a large scale worldwide. Here, the design frequently shows the product’s new characteristics on the one hand, but also follows the corporate design of the brand or product family on the other hand.

The apparent high quality of technical products is increasingly obscure to the consumer (how, for example, can we distinguish one computer chip from another?). For this reason, consumers tend to rely on brand name products. Likewise, customers buying a brand name product trust that the product will suit them and their conception of themselves (and they are therefore part of the target group).

If we look for similar characteristics/correlations between the consumer goods market and the real estate market, the concepts of product image, brand and mobility are particularly interesting.

1. MOBILITY/IMMOBILITY versus BRAND NAME ?

Mobility/Immobility

Mobile telephones and cars work equally well wherever they are. Their design can and must therefore be independent of any local influences and references, and thereby appeals to the broadest possible global target groups. Differentiation between designs and target groups therefore takes place according to criteria such as, for example, gender, age, income, etc.

By contrast, good architecture/the design of buildings makes reference to the locality (genius loci). Adult men and women are potential purchasers or tenants of buildings in equal measure. Architecture which, for instance, only addresses women or young people would therefore be extremely difficult to market.

For this reason, the shape and form of buildings are determined according to completely different principles than for mobile, fast-moving mass consumer goods.

2. BRAND = DEVELOPMENT

In addition to design and/or packaging with a high degree of recognition, brand name products are characterised by their quality, which in the best case scenario is based on long-term research and development. Irrespective of packaging design, the customer, for example, expects the detergent Persil to represent the culmination of the entire experience of the Henkel Group.

Buildings in their entirety are not mass-produced goods. At most, mass-produced goods are installed into them (e.g. sanitary ware, lighting, etc.). Whilst these display the characteristics of brand name products, they do not define the architecture.

Buildings are usually constructed as unique, individual creations and are therefore always prototypes which cannot be the result of long development studies either from a financial or a time point of view.

The situation is only different for prefabricated buildings, which are mass-produced and designed to appeal to specific target groups by the use of conventional architectural clichés (bay windows, windows with glazing bars, fireplaces, pantile roofs). In the cutthroat market of the different prefabricated homes manufacturers, this means the establishment of brand names and images. Huf-Haus projects the brand name image of a company producing high-quality, energy-saving prefabricated houses using plenty of glass and wood, and received praise for this with the reddot design award in 2009.

3. IMAGE = Message

Everywhere where actual or assumed qualities of a product are not visible, i.e. cannot be shown through the design characteristics of the product, product image is necessary or helpful in emphasising the product characteristics and the single defining features (unique selling points).

Today, most consumers are hardly in a position to distinguish between a diesel and a petrol engine or judge the performance of different computers by their appearance. Even fewer are able to judge by the appearance of a building whether it is energy-saving or not. At best, visible indications include photovoltaic conversion equipment or solar energy facilities on house roofs.

4. AIMS

Consequently, the following primary aims initially crystallise for the design and communication of sustainable architecture:

- Improvement of the recognition of all technical constructions and facilities which each contribute to sustainability;

- Improvement of the recognition of the unique design characteristics and special features, including, for example, climatic zones within the buildings, etc.

In addition, it is necessary to always develop sustainable buildings in close cooperation with their intended purpose, i.e.:

- Sustainable architecture must offer new advantages of a sustainable lifestyle to its users;

- Traditional – in particular urban – forms of lifestyle must be fundamentally reconsidered and questioned in the form of visionary scenarios;

- New architectural developments must be a response to different user behaviour patterns in future.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

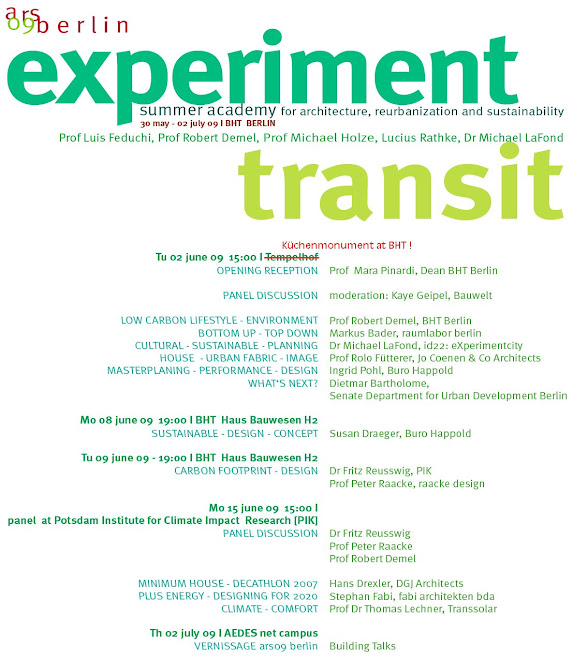

about ars09 berlin

this year SUMMER ACADEMY BERLIN explores architectural strategies towards a low carbon lifestyle. the tempelhof airfield closed in 08 offers the scenario. the size of the airfield calls for transitional answers, change and motion does become one of the targets to be addressed. speakers like Fritz Reusswig from the Potsdam Institute of Climate Impact Research, Thomas Lechner from Transsolar and members of the winning solar decathlon team will be part of the team.

No comments:

Post a Comment